Notes on infinite series of constants.

Infinite Series

An infinite series, or simply a series, is an expression of the form \begin{equation} a_1+a_2+\dots+a_n+\dots=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}a_n \end{equation}

Examples

- Infinite decimal. \begin{equation} .a_1a_2\ldots a_n\ldots=\dfrac{a_1}{10}+\dfrac{a_2}{10^2}+\ldots+\dfrac{a_n}{10^n}+\ldots, \end{equation} where $a_i\in\{0,1,\dots,9\}$.

- Power series expansion

- Geometric series. \begin{equation} \dfrac{1}{1-x}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}x^n=1+x+x^2+x^3+\dots,\hspace{1cm}\vert x\vert<1 \end{equation}

- Exponential function. \begin{equation} {\rm e}^x=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\dfrac{x^n}{n!}=1+x+\dfrac{x^2}{2!}+\dfrac{x^3}{3!}+\ldots \end{equation}

- Sine and cosine formulas. \begin{align} \sin x&=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\dfrac{(-1)^n x^{2n+1}}{(2n+1)!}=x-\dfrac{x^3}{3!}+\dfrac{x^5}{5!}-\dfrac{x^7}{7!}+\ldots \\ \cos x&=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\dfrac{(-1)^n x^{2n}}{(2n)!}=1-\dfrac{x^2}{2!}+\dfrac{x^4}{4!}-\dfrac{x^6}{6!}+\ldots \end{align}

Convergent Sequences

Sequences

If to each positive integer $n$ there corresponds a definite number $x_n$, then the $x_n$’s are said to form a sequence (denoted as $\{x_n\}$) \begin{equation} x_1,x_2,\dots,x_n,\dots \end{equation} We call the numbers constructing a sequence its terms, where $x_n$ is the $n$-th term.

A sequence $\{x_n\}$ is said to be bounded if there exists $A, B$ such that $A\leq x_n\leq B, \forall n$. $A, B$ respectively are called lower bound, upper bound of the sequence. A sequence that is not bounded is said to be unbounded.

Limits of Sequences

A sequence $\{x_n\}$ is said to have a number $L$ as limit if for each $\epsilon>0$, there exists a positive integer $n_0$ that \begin{equation} \vert x_n-L\vert<\epsilon\hspace{1cm}n\geq n_0 \end{equation} We say that $x_n$ converges to $L$ as $n$ approaches infinite ($x_n\to L$ as $n\to\infty$) and denote this as \begin{equation} \lim_{n\to\infty}x_n=L \end{equation}

- A sequence is said to converge or to be convergent if it has a limit.

- A convergent sequence is bounded, but not all bounded sequences are convergent.

- If $x_n\to L,y_n\to M$, then \begin{align} &\lim(x_n+y_n)=L+M \\ &\lim(x_n-y_n)=L-M \\ &\lim x_n y_n=LM \\ &\lim\dfrac{x_n}{y_n}=\dfrac{L}{M}\hspace{1cm}M\neq0 \end{align}

- An increasing (or decreasing) sequence converges if and only if it is bounded.

Convergent and Divergent Series

Recall from the previous sections that if $a_1,a_2,\dots,a_n,\dots$ is a sequence of numbers, then \begin{equation} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}a_n=a_1+a_2+\ldots+a_n+\ldots\tag{1}\label{1} \end{equation} is called an infinite series. We begin by establishing the sequence of partial sums \begin{align} s_1&=a_1 \\ s_2&=a_1+a_2 \\ &\hspace{0.1cm}\vdots \\ s_n&=a_1+a_2+\dots+a_n \\ &\hspace{0.1cm}\vdots \end{align} The series \eqref{1} is said to be convergent if the sequences $\{s_n\}$ converges. And if $\lim s_n=s$, then we say that \eqref{1} converges to $s$, or that $s$ is the sum of the series. \begin{equation} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}a_n=s \end{equation} If the series does not converge, we say that it diverges or is divergent, and no sum is assigned to it.

Examples (harmonic series)

Let’s consider the convergence of harmonic series

\begin{equation}

\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n}=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{3}+\ldots\tag{2}\label{2}

\end{equation}

Let $m$ be a positive integer and choose $n>2^{m+1}$. We have

\begin{align}

s_n&>1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{4}+\dots+\frac{1}{2^{m+1}} \\ &=\left(1+\frac{1}{2}\right)+\left(\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{4}\right)+\left(\frac{1}{5}+\ldots+\frac{1}{8}\right)+\ldots+\left(\frac{1}{2^m+1}+\ldots+\frac{1}{2^{m+1}}\right) \\ &>\frac{1}{2}+2.\frac{1}{4}+4.\frac{1}{8}+\ldots+2^m.\frac{1}{2^{m+1}} \\ &=(m+1)\frac{1}{2}

\end{align}

This proves that $s_n$ can be made larger than the sum of any number of $\frac{1}{2}$’s and therefore as large as we please, by taking $n$ large enough, so the $\{s_n\}$ are unbounded, which leads to that \eqref{2} is a divergent series.

\begin{equation}

\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n}=1+\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{3}+\ldots=\infty

\end{equation}

The simplest general principle that is useful to study the convergence of a series is the $\mathbf{n}$-th term test.

$\mathbf{n}$-th term test

If the series $\{a_n\}$ converges, then $a_n\to 0$ as $n\to\infty$; or equivalently, if $\neg(a_n\to0)$ as $n\to\infty$, then the series must necessarily diverge.

Proof

When $\{a_n\}$ converges, as $n\to\infty$ we have

\begin{equation}

a_n=s_n-s_{n-1}\to s-s=0

\end{equation}

This result shows that $a_n\to 0$ is a necessary condition for convergence. However, it is not a sufficient condition; i.e. it does not imply the convergence of the series when $a_n\to 0$ as $n\to\infty$.

General Properties of Convergent Series

- Any finite number of $0$'s can be inserted or removed anywhere in a series without affecting its convergence behavior or its sum (in case it converges).

- When two convergent series are added term by term, the resulting series converges to the expected sum; i.e. if $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}a_n=s$ and $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}b_n=t$, then

\begin{equation}

\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}(a_n+b_n)=s+t

\end{equation}

Proof

Let $\{s_n\}$ and $\{t_n\}$ respectively be the sequences of partial sums of $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}a_n$ and $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}b_n$. As $n\to\infty$ we have \begin{align} (a_1+b_1)+(a_2+b_2)+\dots+(a_n+b_n)&=\sum_{i=1}^{n}a_i+\sum_{i=1}^{n}b_i \\ &=s_n+t_n\to s+t \end{align} - Similarly, $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}(a_n-b_n)=s-t$ and $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}ca_n=cs$ for any constant $c$.

- Any finite number of terms can be added or subtracted at the beginning of a convergent series without disturbing its convergence, and the sum of various series are related in the expected way.

Proof

If $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}a_n=s$, then \begin{equation} \lim_{n\to\infty}(a_0+a_1+a_2+\dots+a_n)=\lim_{n\to\infty} a_0+\lim_{n\to\infty}(a_1+a_2+\dots+a_n)=a_0+s \end{equation}

Series of Nonnegative terms. Comparison Tests

The easiest infinite series to work with are those whose terms are all nonnegative numbers. The reason, as we saw in the above section, is that if $a_n\geq0$, then the series $\sum a_n$ converges if and only if its sequence $\{s_n\}$ of partial sums is bounded (since $s_{n+1}=s_n+a_{n+1}$).

Thus, in order to establish the convergence of a series of nonnegative terms, it suffices to show that its terms approach zero fast enough, or at least as fast as the terms of a known convergent series of nonnegative terms to keep the partial sums bounded.

Comparison test

If $0\leq a_n\leq b_n$, then

- $\sum a_n$ converges if $\sum b_n$ converges.

- $\sum b_n$ diverges if $\sum a_n$ diverges.

Proof

If $s_n, t_n$ respectively are the partial sums of $\sum a_n,\sum b_n$, then

\begin{equation}

0\leq s_n=\sum_{i=1}^{n}a_i\leq\sum_{i=1}^{n}b_i=t_n

\end{equation}

Then if $\{t_n\}$ is bounded, then so is $\{s_n\}$; and if $\{s_n\}$ is unbounded, then so is $\{t_n\}$.

Example

Consider convergence behavior of two series

\begin{equation}

\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{2^n+1};\hspace{2cm}\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{\ln n}

\end{equation}

The first series converges, because

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{2^n+1}<\frac{1}{2^n}

\end{equation}

and $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{2^n}=1$, which is a convergent series. At the same time, the second series diverges, since

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{n}\leq\frac{1}{\ln n}

\end{equation}

and $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n}$ diverges.

One thing worth remarking is that the condition $0\leq a_n\leq b_n$ for the comparison test need not hold for all $n$, but only for all $n$ from some point on.

The comparison test is simple, but in some cases where it is difficult to establish the necessary inequality between the $n$-th terms of the two series. And since limits are often easier to work with than inequalities, we have the following test.

Limit comparison test

If $\sum a_n,\sum b_n$ are series with positive terms such that \begin{equation} \lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{a_n}{b_n}=1\tag{3}\label{3} \end{equation} then either both series converge or both series diverge.

Proof

we observe that \eqref{3} implies that for all sufficient large $n$, we have

\begin{align}

\frac{1}{2}&\leq\frac{a_n}{b_n}\leq 2 \\ \text{or}\hspace{1cm}\frac{1}{2}b_n&\leq a_n\leq 2b_n

\end{align}

which leads to the fact that $\sum a_n$ and $\sum b_n$ have the same convergence behavior.

The condition \eqref{3} can be generalized by \begin{equation} \lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{a_n}{b_n}=L, \end{equation} where $0<L<\infty$.

Example ($p$-series)

Consider the convergence behavior of the series

\begin{equation}

\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}\dfrac{1}{n^p}=1+\dfrac{1}{2^p}+\dfrac{1}{3^p}+\dfrac{1}{4^p}+\ldots,\tag{4}\label{4}

\end{equation}

where $p$ is a positive constant.

If $p\leq 1$, then $n^p\leq n$ or $\frac{1}{n}\leq\frac{1}{n^p}$. Thus, by comparison with the harmonic series $\sum\frac{1}{n}$, we have that \eqref{4} diverges.

If $p>1$, let $n$ be given and choose $m$ so that $n<2^m$. Then \begin{align} s_n&\leq s_{2^m-1} \\ &=1+\left(\dfrac{1}{2^p}+\dfrac{1}{3^p}\right)+\left(\dfrac{1}{4^p}+\ldots+\dfrac{1}{7^p}\right)+\ldots+\left[\dfrac{1}{(2^{m-1})^p}+\ldots+\dfrac{1}{(2^m-1)^p}\right] \\ &\leq 1+\dfrac{2}{2^p}+\dfrac{4}{4^p}+\ldots+\dfrac{2^{m-1}}{(2^{m-1})^p} \end{align} Let $a=\frac{1}{2^{p-1}}$, then $a<1$ since $p>1$, and \begin{equation} s_n\leq 1+a+a^2+\ldots+a^{m-1}=\dfrac{1-a^m}{1-a}<\dfrac{1}{1-a} \end{equation} which proves that $\{s_n\}$ has an upper bound. Thus \eqref{4} converges.

Theorem 1

If a convergent series of nonnegative terms is rearranged in any manner, then the resulting series also converges and has the same sum.

Proof

Consider two series $\sum a_n$ and $\sum b_n$, where $\sum a_n$ is a convergent series of nonnegative terms and $\sum b_n$ is formed form $\sum a_n$ by rearranging its terms.

Let $p$ be a positive integer and consider the $p$-partial sum of $\sum b_n$, i.e. \begin{equation} t_p=b_1+\ldots+b_p \end{equation} Since each $b$ is some $a$, then there exists an $m$ such that each term in $t_p$ is one of the terms in $s_m=a_1+\ldots+a_m$. This shows us that $t_p\leq s_m\leq s$. Thus, $\sum b_n$ converges to a sum $t\leq s$.

On the other hand, $\sum a_n$ is also a rearrangement of $\sum b_n$, so by the same procedure, similarly we have that $s\leq t$, and therefore $t=s$.

The Integral test. Euler’s constant

In this section, we will be going through a more detailed class of infinite series with nonnegative terms which is those whose terms form a decreasing sequence of positive numbers.

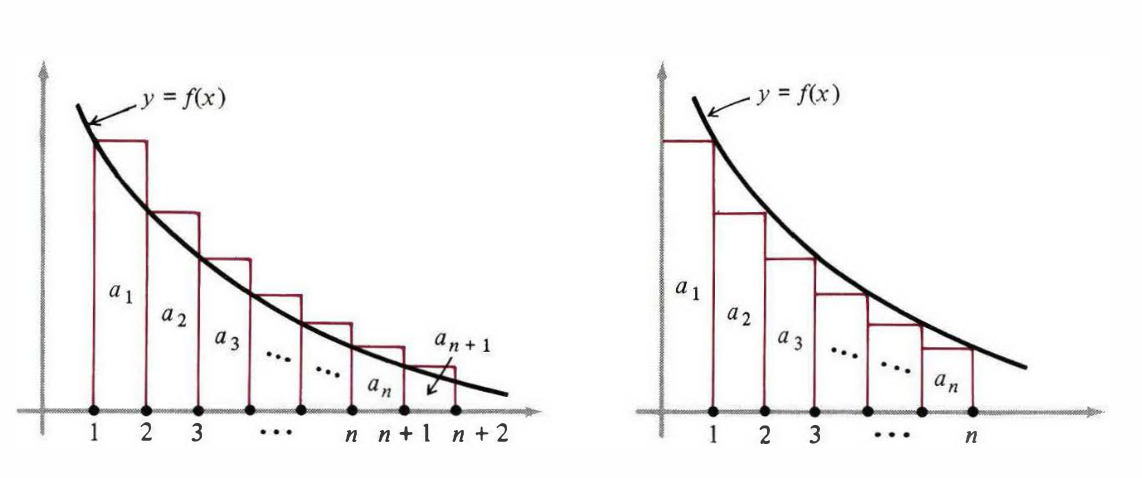

We begin by considering a series \begin{equation} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}a_n=a_1+a_2+\ldots+a_n+\ldots \end{equation} whose terms are positive and decreasing. Suppose $a_n=f(n)$, as shown is Figure 1.

On the left of this figure we see that the rectangles of areas $a_1,a_2,\dots,a_n$ have a greater combined area than the area under the curve from $x=1$ to $x=n+1$, so \begin{equation} a_1+a_2+\dots+a_n\geq\int_{1}^{n+1}f(x)\hspace{0.1cm}dx\geq\int_{1}^{n}f(x)\hspace{0.1cm}dx\tag{5}\label{5} \end{equation} On the right side of the figure, the rectangles lie under the curve, which makes \begin{align} a_2+a_3+\dots+a_n&\leq\int_{1}^{n}f(x)\hspace{0.1cm}dx \\ a_1+a_2+\dots+a_n&\leq a_1+\int_{1}^{n}f(x)\hspace{0.1cm}dx\tag{6}\label{6} \end{align} Putting \eqref{5} and \eqref{6} together we have \begin{equation} \int_{1}^{n}f(x)\hspace{0.1cm}dx\leq a_1+a_2+\dots+a_n\leq a_1+\int_{1}^{n}f(x)\hspace{0.1cm}dx\tag{7}\label{7} \end{equation} The result we obtained in \eqref{7} allows us to establish the integral test.

Integral test

If $f(x)$ is a positive decreasing function for $x\geq1$ such that $f(n)=a_n$ for each positive integer $n$, then the series and integral \begin{equation} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}a_n;\hspace{2cm}\int_{1}^{\infty}f(x)\hspace{0.1cm}dx \end{equation} converge or diverge together.

The integral test holds for any interval of the form $x\geq k$, not just for $x\geq 1$.

Example (Abel’s series)

Let’s consider the convergence behavior of the series

\begin{equation}

\sum_{n=2}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n\ln n}\tag{8}\label{8}

\end{equation}

By the integral test, we have that \eqref{8} diverges, because

\begin{equation}

\sum_{2}^{\infty}\frac{dx}{x\ln x}=\lim_{b\to\infty}\int_{2}^{b}\frac{dx}{x\ln x}=\lim_{b\to\infty}\left(\ln\ln x\Big|_{2}^{b}\right)=\lim_{b\to\infty}\left(\ln\ln b-\ln\ln 2\right)=\infty

\end{equation}

More generally, if $p>0$, then

\begin{equation}

\sum_{n=2}^{\infty}\frac{1}{n(\ln n)^p}

\end{equation}

converges if $p>1$ and diverges if $0<p\leq 1$. For if $p\neq 1$, we have

\begin{align}

\int_{2}^{\infty}\frac{dx}{x(\ln x)^p}&=\lim_{b\to\infty}\int_{2}^{b}\frac{dx}{x(\ln x)^p} \\ &=\lim_{b\to\infty}\left[\dfrac{(\ln x)^{1-p}}{1-p}\Bigg|_2^b\right] \\ &=\lim_{b\to\infty}\left[\dfrac{(\ln b)^{1-p}-(\ln 2)^{1-p}}{1-p}\right]

\end{align}

exists if and only if $p>1$.

Euler’s constant

From \eqref{7} we have that \begin{equation} 0\leq a_1+a_2+\ldots+a_n-\int_{1}^{n}f(x)\hspace{0.1cm}dx\leq a_1 \end{equation} Denoting $F(n)=a_1+a_2+\ldots+a_n-\int_{1}^{n}f(x)\hspace{0.1cm}dx$, the above expression becomes \begin{equation} 0\leq F(n)\leq a_1 \end{equation} Moreover, $\{F(n)\}$ is a decreasing sequence, because \begin{align} &F(n)-F(n+1) \\ &=\left[a_1+a_2+\ldots+a_n-\int_{1}^{n}f(x)\hspace{0.1cm}dx\right]-\left[a_1+a_2+\ldots+a_{n+1}-\int_{1}^{n+1}f(x)\hspace{0.1cm}dx\right] \\ &=\int_{n}^{n+1}f(x)\hspace{0.1cm}dx-a_{n+1}\geq 0, \end{align} where the last step can be seen by observing the right side of Figure 1.

Since any decreasing sequence of nonnegative numbers converges, we have that \begin{equation} L=\lim_{n\to\infty}F(n)=\lim_{n\to\infty}\left[a_1+a_2+\ldots+a_n-\int_{1}^{n}f(x)\hspace{0.1cm}dx\right]\tag{9}\label{9} \end{equation} exists and satisfies the inequalities $0\leq L\leq a_1$.

Let $a_n=\frac{1}{n}$ and $f(x)=\frac{1}{x}$, the last quantity in \eqref{9} becomes \begin{equation} \lim_{n\to\infty}\left(1+\dfrac{1}{2}+\ldots+\dfrac{1}{n}-\ln n\right)\tag{10}\label{10} \end{equation} since \begin{equation} \int_{1}^{n}\dfrac{dx}{x}=\ln x\Big|_1^n=\ln n \end{equation} The value of the limit \eqref{10} is called Euler’s constant (denoted as $\gamma$). \begin{equation} \gamma=\lim_{n\to\infty}\left(1+\dfrac{1}{2}+\ldots+\dfrac{1}{n}-\ln n\right) \end{equation}

The Ratio test. Root test

Ratio test

If $\sum a_n$ is a series of positive terms such that \begin{equation} \lim_{n\to\infty}\dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}=L,\tag{11}\label{11} \end{equation} then

- If $L<1$, the series converges.

- If $L>1$, the series diverges.

- If $L=1$, the test is inconclusive.

Proof

- Let $L<1$ and choose any number $r$ such that $L\lt r\lt 1$. From \eqref{11}, we have that there exists an $n_0$ such that \begin{align} \dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}&\leq r=\dfrac{r^{n+1}}{r_n},\hspace{1cm}\forall n\geq n_0 \\ \dfrac{a_{n+1}}{r^{n+1}}&\leq\dfrac{a_n}{r^n},\hspace{2cm}\forall n\geq n_0 \end{align} which means that $\{\frac{a_n}{r^n}\}$ is a decreasing sequence for $n\geq n_0$; in particular, $\frac{a_n}{r^n}\leq\frac{a_{n_0}}{r^{n_0}}$ for $n\geq n_0$. Thus, if we let $K=\frac{a_{n_0}}{r^{n_0}}$, then we get \begin{equation} a_n\leq Kr^n,\hspace{1cm}\forall n\geq n_0\tag{12}\label{12} \end{equation} However, $\sum Kr^n$ converges since $r<1$. Hence, by the comparison test, \eqref{12} implies that $\sum a_n$ converges.

- When $L>1$, we have that $\frac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}\geq 1$, or equivalently $a_{n+1}\geq a_n$, for all $n\geq n_0$, for some constant $n_0$. That means $\neg(a_n\to 0)$ as $n\to\infty$ (since $\sum a_n$ is a series of positive terms). By the $n$-th term test, it follows that the series diverges.

- Consider the $p$-series $\sum\frac{1}{n^p}$. For all values of $p$, as $n\to\infty$ we have \begin{equation} \dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}=\dfrac{n^p}{(n+1)^p}=\left(\dfrac{n}{n+1}\right)^p\to 1 \end{equation} As in the above example, we have that this series converges if $p>1$ and diverges if $p\leq 1$.

Root test

If $\sum a_n$ is a series of nonnegative terms such that \begin{equation} \lim_{n\to\infty}\sqrt[n]{a_n}=L,\tag{13}\label{13} \end{equation} then

- If $L<1$, the series converges.

- If $L>1$, the series diverges.

- If $L=1$, the test is inconclusive.

Proof

- Let $L<1$ and $r$ is any number such that $L\lt r\lt 1$. From \eqref{13}, we have that there exist $n_0$ such that \begin{align} \sqrt[n]{a_n}&\leq r<1,\hspace{1cm}\forall n\geq n_0 \\ a_n&\leq r^n>1,\hspace{1cm}\forall n\geq n_0 \end{align} And since the geometric series $\sum r^n$ converges, we clearly have that $\sum a_n$ also converges.

- If $L>1$, then $\sqrt[n]{a_n}\geq 1$ for all $n\geq n_0$, for some $n_0$, so $a_n\geq 1$ for all $n\geq n_0$. That means as $n\to\infty$, $\neg(a_n\to 0)$. Therefore, by the $n$-th term test, we have that the series diverges.

- For $L=1$, we provide 2 examples. One is the divergent series $\sum\frac{1}{n}$ and the other is the convergent series $\sum\frac{1}{n^2}$ (since $\sqrt[n]{n}\to 1$ as $n\to\infty$).

The Extended Ratio tests of Raabe and Gauss

Kummer’s theorem

Theorem 2 (Kummer’s)

Assume that $a_n>0,b_n>0$ and $\sum\frac{1}{b_n}$ diverges. If

\begin{equation}

\lim\left(b_n-\dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}.b_{n+1}\right)=L,\tag{14}\label{14}

\end{equation}

then $\sum a_n$ converges if $L>0$ and diverges if $L<0$.

Proof

- If $L>0$, then there exists $h$ such that $L>h>0$. From \eqref{14}, for some positive integer $n_0$ we have

\begin{align}

b_n-\dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}.b_{n+1}&\geq h>0,\hspace{1cm}\forall n\geq n_0 \\ a_n b_n-a_{n+1}b_{n+1}&\geq ha_n>0,\hspace{1cm}\forall n\geq n_0\tag{15}\label{15}

\end{align}

Hence, $\{a_n b_n\}$ is a decreasing sequence of positive numbers for $n\geq n_0$, so $K=\lim a_n b_n$ exists.

Moreover, we have that \begin{equation} \sum_{n=n_0}^{\infty}a_nb_n-a_{n+1}b_{n+1}=a_{n_0}b_{n_0}-\lim_{n\to\infty}a_nb_n=a_{n_0}b_{n_0}-K \end{equation} Therefore, by \eqref{15} and comparison test, we can conclude that $\sum ha_n$ converges, which means that $\sum a_n$ also converges. - If $L<0$, for some positive integer $n_0$ we have \begin{equation} a_nb_n-a_{n+1}b_{n+1}\leq 0,\hspace{1cm}\forall n\geq n_0 \end{equation} Hence, $\{a_nb_n\}$ is a increasing sequence of positive number for all $n\geq n_0$, for some positive integer $n_0$. This also means for all $n\geq n_0$, \begin{align} a_nb_n&\geq a_{n_0}b_{n_0} \\ a_n&\geq (a_{n_0}b_{n_0}).\dfrac{1}{b_n} \end{align} Therefore, $\sum a_n$ diverges (since $\sum\frac{1}{b_n}$ diverges).

Raabe’s test

Theorem 3 (Raabe’s test)

If $a_n>0$ and

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}=1-\dfrac{A}{n}+\dfrac{A_n}{n},

\end{equation}

where $A_n\to 0$, then $\sum a_n$ converges if $A>1$ and diverges if $A<1$.

Proof

Take $n=b_n$ in Kummber’s theorem. Then

\begin{align}

\lim\left(b_n-\dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}.b_{n+1}\right)&=\lim\left[n-\left(1-\dfrac{A}{n}+\dfrac{A_n}{n}\right)(n+1)\right] \\ &=\lim\left[-1+\dfrac{A(n+1)}{n}-\dfrac{A_n(n+1)}{n}\right] \\ &=A-1

\end{align}

and by Kummer’s theorem we have that $\sum a_n$ converges if $A>1$ and diverges if $A<1$.

Raabe’s test can be formulated as followed: If $a_n>0$ and \begin{equation} \lim n\left(1-\dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}\right)=A, \end{equation} then $\sum a_n$ converges if $A>1$ and diverges if $A<1$.

When $A=1$ in Raabe’s test, we turn to Gauss’s test

Gauss’s test

Theorem 4

If $a_n>0$ and

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}=1-\dfrac{A}{n}+\dfrac{A_n}{n^{1+c}},

\end{equation}

where $c>0$ and $A_n$ is bounded as $n\to\infty$, then $\sum a_n$ converges if $A>1$ and diverges if $A\leq 1$.

Proof

- If $A\neq 1$, the statement follows exactly from Raabe's test, since $\frac{A_n}{n^c}\to 0$ as $n\to\infty$.

- If $A=1$, we begin by taking $b_n=n\ln n$ in Kummer's theorem. Then \begin{align} \lim\left(b_n-\dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}.b_{n+1}\right)&=\lim\left[n\ln n-\left(1-\dfrac{1}{n}+\dfrac{A_n}{n^{1+c}}\right)(n+1)\ln(n+1)\right] \\ &=\lim\left[n\ln n-\dfrac{n^2-1}{n}\ln(n+1)-\dfrac{n+1}{n}.\dfrac{A_n\ln(n+1)}{n^c}\right] \\ &=\lim\left[n\ln\left(\dfrac{n}{n+1}\right)+\dfrac{\ln(n+1)}{n}-\dfrac{n+1}{n}.\dfrac{A_n\ln(n+1)}{n^c}\right] \\ &=-1+0-0=-1<0, \end{align} which, by Kummer's theorem, we have that the series is divergent.

In the fourth step we have used the Stolz–Cesàro theorem1.

Theorem 5 (Gauss’s test)

If $a_n>0$ and

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}=\dfrac{n^k+\alpha n^{k-1}+\ldots}{n^k+\beta n^{k-1}+\ldots},\tag{16}\label{16}

\end{equation}

then $\sum a_n$ converges if $\beta-\alpha>1$ and diverges if $\beta-\alpha\leq 1$.

Proof

If the quotient on the right of \eqref{16} is worked out by long division, we get

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{a_{n+1}}{a_n}=1-\dfrac{\beta-\alpha}{n}+\dfrac{A_n}{n^2},

\end{equation}

where $A_n$ is a quotient of the form

\begin{equation}

\dfrac{\gamma n^{k-2}+\ldots}{n^{k-2}+\ldots}

\end{equation}

and is therefore clearly bounded as $n\to\infty$. The statement now follows from Theorem 4 with $c=1$.

The Alternating Series test. Absolute Convergence

Previously, we have been working with series of positive terms and nonnegative terms. It’s time to consider series with both positive and negative terms. The simplest are those whose terms are alternatively positive and negative.

Alternating Series

Alternating series is series with the form \begin{equation} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n+1}a_n=a_1-a_2+a_3-a_4+\ldots,\tag{17}\label{17} \end{equation} where $a_n$’s are all positive numbers.

From the definition of alternating series, we establish alternating series test.

Alternating Series test

If the alternating series \eqref{17} has the property that

- $a_1\geq a_2\geq a_3\geq\ldots$

- $a_n\to 0$ as $n\to\infty$

then $\sum a_n$ converges.

Proof

On the one hand, we have that a typical even partial sum $s_{2n}$ can be written as

\begin{equation}

s_{2n}=(a_1-a_2)+(a_3-a_4)+\ldots+(a_{2n-1}-a_{2n}),

\end{equation}

where each expression in parentheses is nonnegative since $\{a_n\}$ is a decreasing sequence. Hence, we also have that $s_{2n}\leq s_{2n+2}$, which leads to the result that the even partial sums form an increasing sequence.

Moreover, we can also display $s_{2n}$ as \begin{equation} s_{2n}=a_1-(a_2-a_3)-(a_4-a_5)-\ldots-(a_{2n-2}-a_{2n-1})-a_{2n}, \end{equation} where each expression in parentheses once again is nonnegative. Thus, we have that $s_{2n}\leq a_1$, so ${s_{2n}}$ has an upper bound. Since every bounded increasing sequence converges, there exists a number $s$ such that \begin{equation} \lim_{n\to\infty}s_{2n}=s \end{equation}

On the other hand, the odd partial sums approach the same limit, because \begin{align} s_{2n+1}&=a_1-a_2+a_3-a_4+\ldots-a_{2n}+a_{2n+1} \\ &=s_{2n}+a_{2n+1} \end{align} and therefore \begin{equation} \lim_{n\to\infty}s_{2n+1}=\lim_{n\to\infty}s_{2n}+\lim_{n\to\infty}a_{2n+1}=s+0=s \end{equation} Since both sequence of even sums and sequence of odd partial sums converges to $s$ as $n$ tends to infinity, this shows us that $\{s_n\}$ also converges to $s$, and therefore the alternating series \eqref{17} converges to the sum $s$.

Absolute Convergence

A series $\sum a_n$ is said to be absolutely convergent if $\sum\vert a_n\vert$ converges.

These are some properties of absolute convergence.

- Absolute convergence implies convergence.

Proof

Suppose that $\sum a_n$ is an absolutely convergent series, or $\sum\vert a_n\vert$ converges. We have that \begin{equation} 0\leq a_n+\vert a_n\vert\leq 2\vert a_n\vert \end{equation} And since $\sum 2\vert a_n\vert$ converges, by comparison test, we also have that $\sum(a_n+\vert a_n\vert)$ converges. Since both $\sum\vert a_n\vert$ and $\sum(a_n+\vert a_n\vert)$ converge, so does their difference, which is $\sum a_n$. - A convergent series that is not absolutely convergent is said to be conditionally convergent.

- Any conditionally convergent series can be made to converge to any given number as its sum, or even to diverge, by suitably changing the order of its terms without changing the terms themselves (check out Theorem 8 to see the proof).

- On the other hand, any absolutely convergent series can be rearranged in any manner without changing its convergence behavior or its sum (check out Theorem 7 to see the proof).

Absolute vs Conditionally Convergence

Theorem 6

Consider a series $\sum a_n$ and define $p_n$ and $q_n$ by

\begin{equation}

p_n=\dfrac{\vert a_n\vert+a_n}{2},\hspace{2cm}q_n=\dfrac{\vert a_n\vert-a_n}{2}

\end{equation}

Then

- If $\sum a_n$ converges conditionally, then both $\sum p_n$ and $\sum q_n$ diverges.

- If $\sum a_n$ converges absolutely, then $\sum p_n$ and $\sum q_n$ both converge and the sums of these series are related by the equation \begin{equation} \sum a_n=\sum p_n-\sum q_n \end{equation}

Proof

From the formulas of $p_n$ and $q_n$, we have

\begin{align}

a_n&=p_n-q_n\tag{18}\label{18} \\ \vert a_n\vert&=p_n+q_n\tag{19}\label{19}

\end{align}

We begin by proving the first statement.

- When $\sum a_n$ converges, from \eqref{18}, we have $\sum p_n$ and $\sum q_n$ both must have the same convergence behavior (i.e. converge or diverge at the same time).

If they both converge, then from \eqref{19}, we have that $\sum\vert a_n\vert$ converges, contrary to the hypothesis, so $\sum p_n$ and $\sum q_n$ are both divergent. - To prove the second statement, we assume that $\sum\vert a_n\vert$ converges. We have \begin{equation} p_n=\dfrac{\vert a_n\vert+a_n}{2}\leq\dfrac{2\vert a_n\vert}{2}=\vert a_n\vert \end{equation} which shows us that $\sum p_n$ converges. Similarly, for $q_n$, we have \begin{equation} q_n=\dfrac{\vert a_n\vert-a_n}{2}\leq\dfrac{2\vert a_n\vert}{2}=\vert a_n\vert \end{equation} which also lets us obtain that $\sum q_n$ converges. Hence \begin{equation} \sum p_n-\sum q_n=\sum(p_n-q_n)=\sum a_n \end{equation}

Theorem 7

If $\sum a_n$ is an absolutely convergent series with sum $s$, and if $a_n$’s are rearranged in any way to from a new series $\sum b_n$, then this new series is also absolutely convergent with sum $s$.

Proof

Since $\sum\vert a_n\vert$ is a convergent series of nonnegative terms with sum $s$ and since the $b_n$’s are just the $a_n$’s in a different order, it follows from Theorem 1 that $\sum\vert b_n\vert$ also converges to $s$. Therefore $\sum b_n$ is absolutely convergent with sum $t$, for some positive $t$.

Theorem 6 allows us to write \begin{equation} s=\sum a_n=\sum p_n-\sum q_n, \end{equation} and \begin{equation} t=\sum b_n=\sum P_n-\sum Q_n, \end{equation} where each of the series on the right is convergent and consists of nonnegative. But the $P_n$’s and $Q_n$’s are simply the $p_n$’s and $q_n$’s in a different order. Hence, by Theorem 1, we have $\sum P_n=\sum p_n$ and $\sum Q_n=\sum q_n$. And therefore, $t=s$.

Theorem 8 (Riemann’s rearrangement theorem)

Let $\sum a_n$ be a conditionally convergent series. Then its terms can be rearranged to yield a convergent series whose sum is an arbitrary preassigned number, or a series that diverges to $\infty$, or a series that diverges to $-\infty$.

Proof

Since $\sum a_n$ converges conditionally, we begin by using Theorem 6 to form the two divergent series of nonnegative terms $\sum p_n$ and $\sum q_n$.

To prove the first statement, let $s$ be any number and construct a rearrangement of the given series as follows. Start by writing down $p$’s in order until the partial sum \begin{equation} p_1+p_2+\ldots+p_{n_1} \end{equation} is first $\geq s$; next we continue with $-q$’s until the total partial sum \begin{equation} p_1+p_2+\ldots+p_{n_1}-q_1-q_2-\ldots-q_{m_1} \end{equation} is first $\leq s$; then we continue with $p$’s until the total partial sum \begin{equation} p_1+\ldots+p_{n_1}-q_1-\ldots-q_{m_1}+p_{n_1+1}+\ldots+p_{n_2} \end{equation} is first $\geq s$; and so on.

The possibility of each of these steps is guaranteed by the divergence of $\sum p_n$ and $\sum q_n$; and the resulting rearrangement of $\sum a_n$ converges to $s$ because $p_n\to 0$ and $q_n\to 0$.In order to make the rearrangement diverge to $\infty$, it suffices to write down enough $p$’s to yield \begin{equation} p_1+p_2+\ldots+p_{n_1}\geq 1, \end{equation} then to insert $-q_1$, and then to continue with $p$’s until \begin{equation} p_1+\ldots+p_{n_1}-q_1+p_{n_1+1}+\ldots+p_{n_2}\geq 2, \end{equation} then to insert $-q_2$, and so on.

We can produce divergence to $-\infty$ by a similar construction.

One of the principal application of Theorem 7 relates to the multiplication of series.

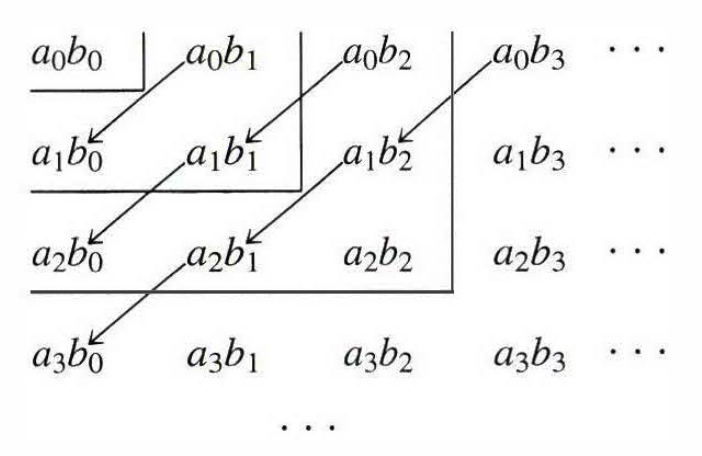

If we multiply two series \begin{align} \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}a_n&=a_0+a_1+\ldots+a_n+\ldots\tag{20}\label{20} \\ \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}b_n&=b_0+b_1+\ldots+b_n+\ldots\tag{21}\label{21} \end{align} by forming all possible product $a_i b_j$ (as in the case of finite sums), then we obtain the following doubly infinite array

There are various ways of arranging these products into a single infinite series, of which two are important. The first one is to group them by diagonals, as indicated in the arrows in Figure 2: \begin{equation} a_0b_0+(a_0b_1+a_1b_1)+(a_0b_2+a_1b_1+a_2b_0)+\ldots\tag{22}\label{22} \end{equation} This series can be defined as $\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}c_n$, where \begin{equation} c_n=a_0b_n+a_1b_{n-1}+\ldots+a_nb_0 \end{equation}

It is called the product (or Cauchy product) of the two series $\sum a_n$ and $\sum b_n$.

The second crucial method of arranging these products into a series is by squares, as shown in Figure 2:

\begin{equation}

a_0b_0+(a_0b_1+a_1b_1+a_1b_0)+(a_0b_2+a_1b_2+a_2b_2+a_2b_1+a_2b_0)+\ldots\tag{23}\label{23}

\end{equation}

The advantage of this arrangement is that the $n$-th partial sum $s_n$ of \eqref{23} is given by

\begin{equation}

s_n=(a_0+a_1+\ldots+a_n)(b_0+b_1+\ldots+b_n)\tag{24}\label{24}

\end{equation}

Theorem 9

If the two series \eqref{20} and \eqref{21} have nonnegative terms and converges to $s$ and $t$, then their product \eqref{22} converges to $st$.

Proof

It is clear from \eqref{24} that \eqref{23} converges to $st$. Let’s denote the series \eqref{22} and \eqref{23} without parenthesis by $(22’)$ and $(23’)$.

We have the series $(23’)$ of nonnegative terms still converges to $st$ because, for if $m$ is an integer such that $n^2\leq m\leq (n+1)^2$, then the $m$-th partial sum of $(23’)$ lies between $s_{n-1}$ and $s_n$, and both of these converge to $st$.

By Theorem 7, the terms of $(23’)$ can be rearranged to yield $(22’)$ without changing the sum $st$; and when parentheses are suitably inserted, we see that \eqref{8} converges to $st$.

We now extend Theorem 9 to the case of absolute convergence.

Theorem 10

If the series $\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}a_n$ and $\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}b_n$ are absolutely convergent, with sum $s$ and $t$, then their product

\begin{multline}

\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}(a_0b_n+a_1b_{n-1}+\ldots+a_nb_0)=a_0b_0+(a_0b_1+a_1b_0)\hspace{0.1cm}+ \\ (a_0b_2+a_1b_1+a_2b_0)+\ldots+(a_0b_n+a_1b_{n-1}+\ldots+a_nb_0)+\ldots\tag{25}\label{25}

\end{multline}

is absolutely convergent, with sum $st$.

Proof

The series $\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\vert a_n\vert$ and $\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\vert b_n\vert$ are convergent and have nonnegative terms. So by Theorem 9 above, their product

\begin{multline}

\vert a_0\vert\vert b_0\vert+\vert a_0\vert\vert b_1\vert+\vert a_1\vert\vert b_0\vert+\ldots+\vert a_0\vert\vert b_n\vert+\vert a_1\vert\vert b_{n-1}\vert+\ldots+\vert a_n\vert\vert b_0\vert+\ldots \\ =\vert a_0b_0\vert+\vert a_0b_1\vert+\vert a_1b_0\vert+\ldots+\vert a_0b_n\vert+\vert a_1b_{n-1}\vert+\ldots+\vert a_nb_0\vert+\ldots\tag{26}\label{26}

\end{multline}

converges, and therefore the series

\begin{equation}

a_0b_0+a_0b_1+a_1b_0+\ldots+a_0b_n+\ldots+a_nb_0+\ldots\tag{27}\label{27}

\end{equation}

is absolutely convergent. It follows from Theorem 7 that the sum of \eqref{27} will not change if we rearrange its terms and write it as

\begin{equation}

a_0b_0+a_0b_1+a_1b_1+a_1b_0+a_0b_2+a_1b_2+a_2b_2+a_2b_1+a_2b_0+\ldots\tag{28}\label{28}

\end{equation}

We now observe that the sum of the first $(n+1)^2$ terms of \eqref{28} is

\begin{equation}

(a_0+a_1+\ldots+a_n)(b_0+b_1+\ldots+b_n),

\end{equation}

so it is clear that \eqref{28}, and with it \eqref{27}, converges to $st$. Thus, \eqref{25} also converges to $st$, since \eqref{25} is retrieved by suitably inserted parentheses in \eqref{27}.

Moreover, we also have \begin{equation} \vert a_0b_n+a_1b_{n-1}+\ldots+a_nb_0\vert\leq\vert a_0b_n\vert+\vert a_1b_{n-1}\vert+\ldots+\vert a_nb_0\vert \end{equation} and the series \begin{equation} \vert a_0b_0\vert+(\vert a_0b_1\vert+\vert a_1b_0\vert)+\ldots+(\vert a_0b_n\vert+\ldots+\vert a_nb_0\vert)+\ldots \end{equation} obtained from \eqref{26} by inserting parentheses. By the comparison test, \eqref{25} converges absolutely. Hence, we can conclude that \eqref{25} is absolutely convergent, with sum $st$.

We have already gone through convergence tests applied only to series of positive (or nonnegative) terms. Let’s end this lengthy note with the alternating series test. ^^!

Dirichlet’s test

Abel’s partial summation formula

Consider series $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}a_n$, sequence $\{b_n\}$. If $s_n=a_1+a_2+\ldots+a_n$, then \begin{equation} a_1b_1+a_2b_2+\ldots+a_nb_n=s_1(b_1-b_2)+s_2(b_2-b_3)+\ldots+s_{n-1}(b_{n-1}-b_n)+s_nb_n\tag{29}\label{29} \end{equation}

Proof

Since $a_1=s_1$ and $a_n=s_n-s_{n-1}$ for $n>1$, we have

\begin{align}

a_1b_1&=s_1b_1 \\ a_2b_2&=s_2b_2-s_1b_2 \\ a_3b_3&=s_3b_3-s_2b_3 \\ &\vdots \\ a_nb_n&=s_nb_n-s_{n-1}b_n

\end{align}

On adding these equations, and grouping suitably, we obtain \eqref{29}.

Dirichlet’s test

If the series $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}a_n$ has bounded partial sums, and if $\{b_n\}$ is a decreasing sequence of positive numbers such that $b_n\to 0$, then the series \begin{equation} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty}a_nb_n=a_1b_1+a_2b_2+\ldots+a_nb_n+\ldots\tag{30}\label{30} \end{equation} converges.

Proof

Let $S_n=a_1b_1+a_2b_2+\ldots+a_nb_n$ denote the $n$-th partial sum of \eqref{30}, then \eqref{29} tells us that

\begin{equation}

S_n=T_n+s_nb_n,

\end{equation}

where

\begin{equation}

T_n=s_1(b_1-b_2)+s_2(b_2-b_3)+\ldots

\end{equation}

Since ${s_n}$ is bounded there exists a positive constant $m$ such that $\vert s_n\vert\leq m,\forall n$, so $\vert s_nb_n\vert\leq mb_n$. And since $b_n\to 0$, we have that $s_nb_n\to 0$ as $n\to\infty$.

Moreover, since $\{b_n\}$ is a decreasing sequence of positive numbers, we have that \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \vert s_1(b_1-b_2)\vert+\vert s_2(b_3-b_3)\vert+\ldots&\hspace{0.1cm}+\vert s_{n-1}(b_{n-1}-b_n)\vert \\ &\leq m(b_1-b_2)+m(b_2-b_3)+\ldots+m(b_{n-1}-b_n) \\ &=m(b_1-b_n)\leq mb_1 \end{aligned} \end{equation} which implies that $T_n=s_1(b_1-b_2)+s_2(b_2-b_3)+\ldots$ converges absolutely, and thus, it converges to a sum $t$. Therefore \begin{equation} \lim_{n\to\infty}S_n=\lim_{n\to\infty}T_n+s_nb_n=\lim_{n\to\infty}T_n+\lim_{n\to\infty}s_nb_n=t+0=t \end{equation} which lets us conclude that the series \eqref{30} converges.

References

[1] George F.Simmons. Calculus With Analytic Geometry - 2nd Edition.

[2] Marian M. A Concrete Approach to Classical Analysis.

[3] MIT 18.01. Single Variable Calculus.

Footnotes

Theorem (Stolz–Cesaro)

Let $\{a_n\}$ be a sequence of real numbers and $\{b_n\}$ be a strictly monotone and divergent sequence. Then \begin{equation} \lim_{n\to\infty}\dfrac{a_{n+1}-a_n}{b_{n+1}-b_n}=L\hspace{1cm}(\in\left[-\infty,+\infty\right]) \end{equation} implies \begin{equation} \lim_{n\to\infty}\dfrac{a_n}{b_n}=L \end{equation} ↩︎